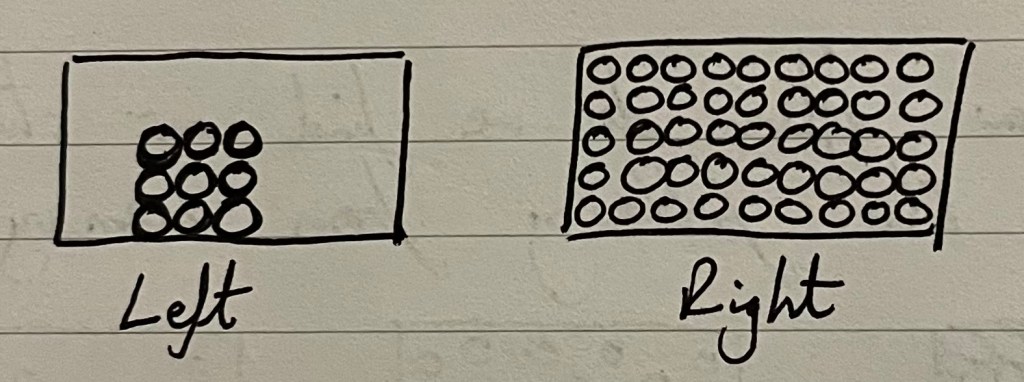

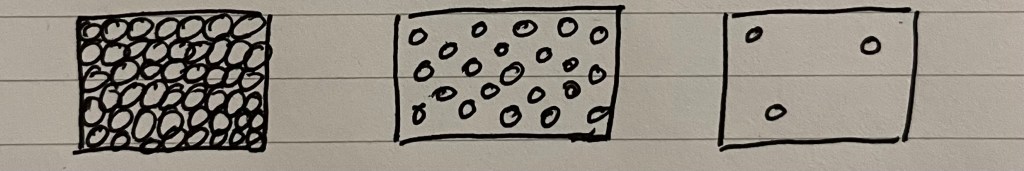

Across the country, countless science teachers have scribbled the 3 box diagram below, ready to introduce, recap or quiz their students about solids, liquids and gases.

But how often do we find our students recreating the following from memory?

What can we discern? They they can imagine particles are really packed in with solids? That they get there’s a lot of empty space in a gas (and perhaps some believe that’s why there’s “not much” to the air around them)? And finally, that they have approximated that liquids must be about halfway between solids and gases, likely because liquid is the middle box. When we see this, we can be near certain that they have divorced their everyday experience of water in a bottle from this abstract representation.

We can do better at highlighting the salient points of each.

Let’s start with the concrete: solids.

Remember that your diagrams allow students to discern the meaning of an idea; students do not encounter solids consisting of just nine particles, but I argue the left diagram is better than the right because:

- It highlights the solid as separate from the ‘container’ of the box. It has order and a fixed shape, independent of the container.

- It gives us space for a side-by-side comparison for its melting into a liquid.

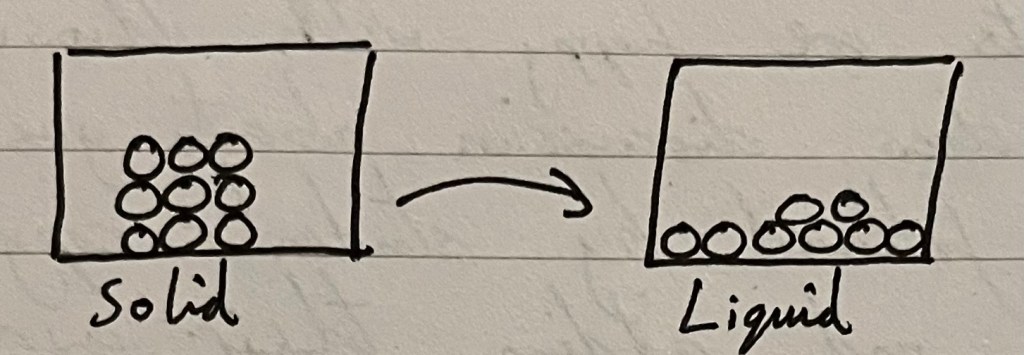

Solids into liquids.

I would draw the following diagram whilst explaining that our solid has melted into a liquid, like ice melting into water.

The best thing about live drawing diagrams is the ability to pepper questions throughout to check for listening and developing understanding:

- What have the particles done now that the solid has melted into a liquid?

- If we froze the liquid back into a solid, what would the shape of the solid be? How would we draw it?

- (Notice in the diagram above: 8 particles in the liquid, when the solid had 9 to start with) I have missed something from the liquid diagram – can you see what it is?

- If I had a box with a sugar cube in it and another slightly filled up with water, what would happen if I tipped the boxes? If we tipped each box in our diagram, what would happen to the particles in the solid? What would happen to the particles in the liquid?

There are questions in this list related to conservation of mass. This may not be the specific learning objective when introducing the particle model, but we can lay the groundwork. A demonstration of an ice cube melting into water and having the same mass on a top pan balance would aid this idea and further link abstract diagrams to real life observations.

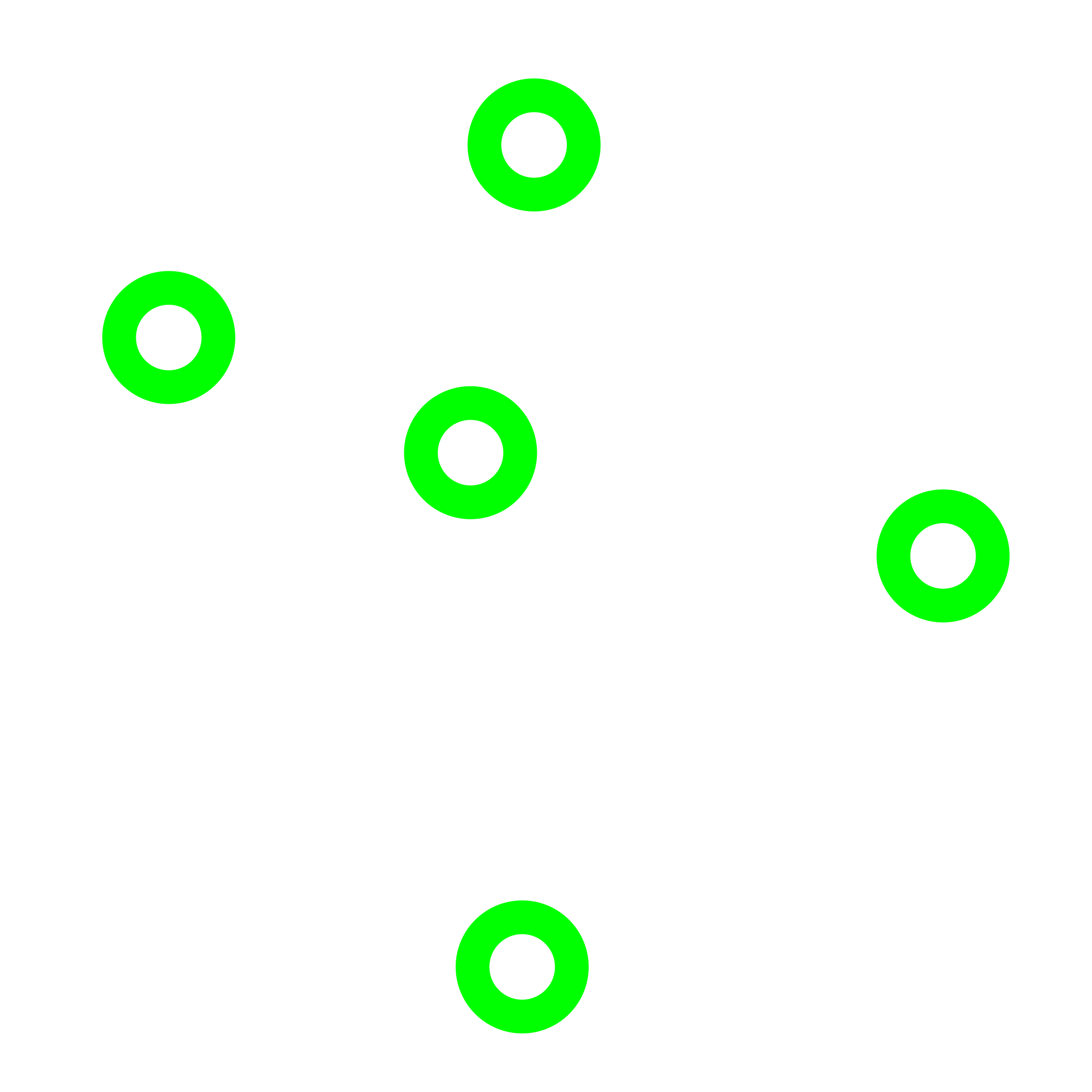

Gassing about gases

Once students are happy with these ideas, a class discussion about gases can be followed by students predicting the particle diagram for gases. They could copy and complete the diagram below, or perhaps mini-whiteboards would be best to show you what all students are mentally picturing.

However you do it, you will have different representations to show the class under a camera (or up near the front of the room).

Observations of student drawing:

- Have they evenly spaced the particles out? If so, students are predicting that gases have an intrinsic order to them. Be explicit about rapid random movement when completing the explanation.

- Are the particles drawn everywhere throughout the box? Gas particles are going to fill their container, no matter the size of the container.

- Are there the same number of particles as in the instigating liquid diagram? Conservation of matter again. If there were 9 particles in your solid, then 9 in your liquid, there are still 9 in your gas. How can gases fill a big container if there are so few particles – there is lots of empty space between them.

Final notes on helping students to make meaning of all this:

Ice to water to steam is perhaps the best real life example to anchor explanation. You must use it… but. I have observed teaching in which a Key Stage 3 class were left baffled at being asked to name the processes by which solids, liquids and gases become each other, yet asking questions such as “What do we call it when ice turns into water?” or, “What do we call it when water becomes steam?” unlocked all the correct terminology. We must provide other examples for our students to generalise these processes. Ice cream melting into cream is great. Many students find it wild that you can boil cream into gases. Just imagine what happens when you help them to truly understand that you can boil steel too.